Horse-based, nomadic cultures:

Mongolians traditionally lead a pastoral, nomadic lifestyle. Because of the climate and short growing season, animal husbandry defines the nomadic lifestyle, with agriculture playing a secondary role. Nomads raise primarily five types of animalsgoats, sheep, cattle (including yaks), camels and horsesthat provide food, dairy products, transportation, and wool.

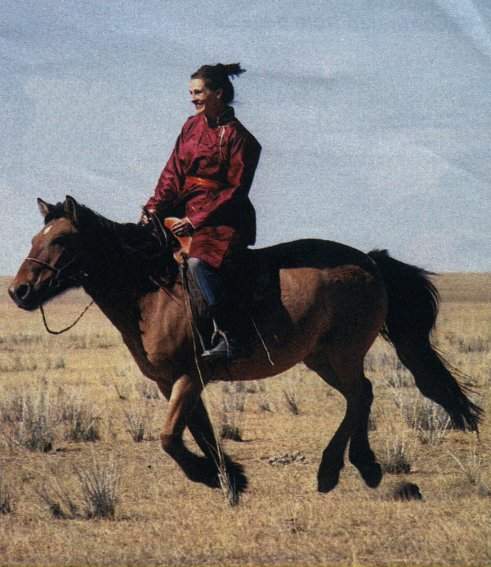

Of these animals, the horse holds the preeminent position in Mongolian hearts and legends. As one of the only remaining horse-based cultures left in the world, Mongolians greatly cherish their horses. Outside the capital, Ulaanbaatar, the horse is still the main mode of transportation and children begin riding as young as three years old. Nomads are extremely proud of their horse riding skills and horseracing is a favorite past time. Believing the race to be a test of the animals, and not the riders, ability, young children are often the jockeys. The most prestigious tests of these superb animals are the horseraces at the Naadam Festival, Mongolias national games, which takes place each July. Families will travel for days to be able to participate or just attend this grand event.

Nomadic families follow a seasonal routine, moving their herds to new grazing land based on the time of year, rather than one of aimless wandering. Historically, each clan had various chosen grazing grounds that were used exclusively by the same clan year after year. This tradition carries on today and families return to the same locations at the same time each year, for example, traveling at the end of each winter from a specific sheltered valley to a particular area on the high plateau of the Steppes.

Daily responsibilities are divided evenly among family members and no one persons work is considered more important than anothers. Traditionally, men take care of the horses and the herds and make saddles, harnesses, and weapons. In addition, they hunt to supplement the traditional diet of dairy products. Womens responsibilities include cooking, taking care of the children, and making clothing (the traditional Mongolian costume is the ankle-length silk del). Women also milk cows, goats, and mares (the national drink is airagfermented mares milk). Despite their enterprise, however, Mongolians are not self-sufficient. Since ancient times, they have traded with surrounding civilizations for grain, rice, tea, silk, cotton, and, above all, metals for their weapons.

Horses and people depend on each other in Mongolia, so there is a mutual respect between them that runs deep and long in Mongolian civilization. Even for someone like me who has had a lifelong passion for horses, my relationship with my own horses now seems somehow new and contrived in comparison. Five thousand years worth of understanding and security forged in one of the harshest environments on earth gives unmatchable authenticity and profundity to a bond between man and animal. In relation to this, mine, I now see, is merely a short, superficial acquaintance.

I made this discovery on a recent trip to Mongolia, and from long conversations with Mongolian racehorse trainers in the Gobi. A group of colleagues and my wife and I, in a modest way, breed thoroughbred race horses in Australia, hence my curiosity. I was particularly interested to see whether the folklore surrounding the breeding of thoroughbreds in Australia would find any parallels in the practices of those who bred and trained racehorses in Mongolia.

There are differences, of course, between the refined catwalk thoroughbreds of Europe and the rough and tough Mongolian racehorse. Like mannequins, thoroughbreds are tall and fragile and highly-strung, and good ones (and bad ones for that matter) are ridiculously expensive. They run short distances and break down frequently. They are molly coddled. Mongolian racehorses, on the other hand, work for a living when they are not racing. When they race, they race longer distances - 30 kilometres over rough terrain, sometimes pitted against hundreds of other horses in the same race. They are ridden by boys and girls of 7 to 13 years of age, who ride for the honour of it not by a special breed of small men (and the occasional woman) who ride for the money and the (vain) glory.

Mongolian horses are uglier too (at least to an eye weaned on long legs and sleek coats, and cropped tails and manes), and shorter, and unkempt, and cost much less. But they are no less highly valued, and they are much more respected by the community as a whole than their more refined foreign cousins are. This makes Mongolian horses (and their owners) seem more at peace with themselves, as if they have a grip on the meaning of life that eludes most thoroughbreds (and their owners!).

In the thoroughbred breeding industry there is the cult of the stallion. Many breeders and most buyers subscribe to the view that the better the stallion the better the foal, and that a good sire can make up for an ordinary dam. This logic owes much to the influence of the market, where stud fees for the best stallions can exceed US$100,000 per foal. This is an obscene amount to pay anywhere, but it seems particularly so when viewed from a Ger in the Mongolian steppe - where a good race horse might cost you $60, and where people who have a job might earn $10 per month. But if youve paid that much to have your mare covered there is a strong incentive to believe that the stallion will do the job, and to persuade others (particularly wealthy buyers) to believe likewise.

Mongolian racehorse trainers breed their own racehorses. They believe that the dam is just as important as the sire, and some believe her to be more important. However, they believe that a horses conformation the way it looks is more important than its breeding. That is to say, that your chances of picking a good (future) race horse are much higher if you put conformation ahead of family. They do not subscribe to the view that a mare that produces one or two good foals is more likely to beget another good one. They believe the overall balance of the horse to be important, and that it should have an easy gait, and a long stride. They also attend to the horses head, to its ears, and to its alertness and personality.

This knowledge is an oral tradition that has been passed down from generation to generation for thousands of years. And, to my surprise, much of what I heard was reassuringly similar to the views of those whose judgement I respect among thoroughbred breeders back home. Like Australians, Mongolians will also swim their horses during preparation for racing. They race them sparingly, and will give them the best available pasture. Unlike Australia, where precocity is paid for with huge wastage (of young horses that break down irreparably), a two-year-old horse is considered too young to race.

There is much more to say about all of this, and what I have said does scant justice to what I was privileged to hear. But this is unpaid work that I do on the aero plane that flies me home between consulting jobs. And the pulse of the market still beats strongly in my veins, drowning out more elemental urgings. I hope one day that this will change, and that I shall be able then to write about the things that really matter, whether I am paid for it or not. I shall return to Mongolia then and spend more time with the horses and their people, and find out more - about them and about myself. I think I yearn for that day.

|  |  |  |

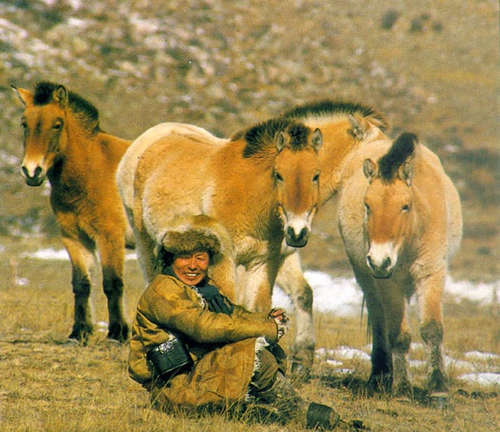

TAKHI (The Mongolian Wild Horse)

Wild horses once roamed in great herds over Mongolia. Numbers declined with increasing competition for pastureland from domesticated livestock. Remnants of herds were gradually pushed into the southern Gobi -- they were discovered there by western explorers at the end of the last century. Living specimens were then exported as novelties to western zoos, where they were bred in captivity. The remaining wild horses in Mongolia were exterminated during the 1950s when hungry soldiers retreating from a failed insurrection in China hunted them for food.

The Mongolian wild horse is regarded by some as a unique species, differing in important ways from other horses in the world. The subject is debated, however, and has taken on a nationalistic tinge due to the symbolic importance of the horse in Mongolia. Research is being done on the genetic makeup of the original animals, and the extent to which genetic purity was maintained during decades of captive breeding. The animals that have now been reintroduced to Mongolia are distinguished by extremely heavy manes and an unusual coloring that allows them to blend into steppe terrain. In winter, the horses are white on their bellies and light-tan colored on their backs; in summer, the light coloring darkens as snow cover on the steppe melts.

In Mongolia, this species of horse is called 'takhi,' a word that reflects a reverence for horses. Takhi means spirit, or spiritual, in Mongolian. The takhi is called the Przewalski horse in Europe and America, after a Polish colonel who explored Siberia and Mongolia for the Russian czar in the last century. Przewalski sent living examples of this horse back to St. Petersburg. European zoos then began to acquire individual horses for their collections. With the extinction of the takhi in its native Mongolia, these zoo animals became the only remaining examples of the species.

At the present time about 1,200 takhi are living in captivity around the world. They have been bred in captivity for 11 to 13 generations. In 1990, a program to reintroduce the takhi into its native homeland was agreed upon between the Mongolian Association for Conservation of Nature and the Environment (MACNE) and a Dutch Foundation that manages six semi-reserves for the horse in the Netherlands and Germany. In 1992 the first thirty-two animals arrived at Hustain Nuruu, a reserve one hundred ilometers west of Ulaanbaatar. They came from reserves in Holland and the Ukraine, and were carefully chosen for genetic variety, in order to produce vital offspring that are as outbred as possible. Further transport of animals has continued since that time and there are now around two hundred takhi living back in Mongolia.

The Hustain Nuruu reserve includes three acclimatization areas, which are large fenced-in areas in semi-mountainous terrain. They incorporate a natural stream that runs through a valley. After one or two seasons in this semi-protected area, horses are released into the wild in 'harems' or groups of mares with one stallion each. In June, 1994, the first two harems were released into the wild and in July, 1995, a third harem was released to complete freedom.

written by Isabel

When I was watching the Mongolia movie I heard that Mongolia people drunk horse milk. I would not like to live there because it's too much work, too chilly and too windy. I learned that children race other children. When they put their ger down it only takes one hour. A ger is their house. They cook with horse dung because there are no trees. The ground is flat and if you walk very far everything looks the same. If you want to go to the bathroom it's everywhere outside. Their food is called curd, cheese and meat and it is very good if they eat meat. They do not have that much fruit.

by Shivaani

In Mongolia they work together. In Mongolia they go to the bathroom outside their house. In Mongolia they sometimes ride horses. Julia Roberts is a very nice person. The Mongolian people gave Julia Roberts a drink and she said it tasted like liquid yogurt. She went to visit Mongolia. I think she likes it in Mongolia. They did a horse race and one of the Mongolian people won the race. After that Julia Roberts taught the children a game called ring around the rosy. In Mongolia they do not have dishes. It is winter in Mongolia. I wish I can go and visit Mongolia.

by Ife

Julia has been riding horses since she was four years old. She said horses can give speed and power. They can communicate with their ears and they can show you signs. She stayed with a family. When she went inside the ger they made some airag. When she tried it I don't think she liked it. The guests get their own ger. When she says, "Where is the bathroom?" she sees a little boy using the bathroom outside. Then she said there's the bathroom. When it is morning they pack Ms. Roberts's ger. They all work together to pack it all on a camel. It takes an hour. The camel can go a whole week without water and a whole month without food and they can walk 13 miles.

|

|  |  |  | |